Lost Women of Science

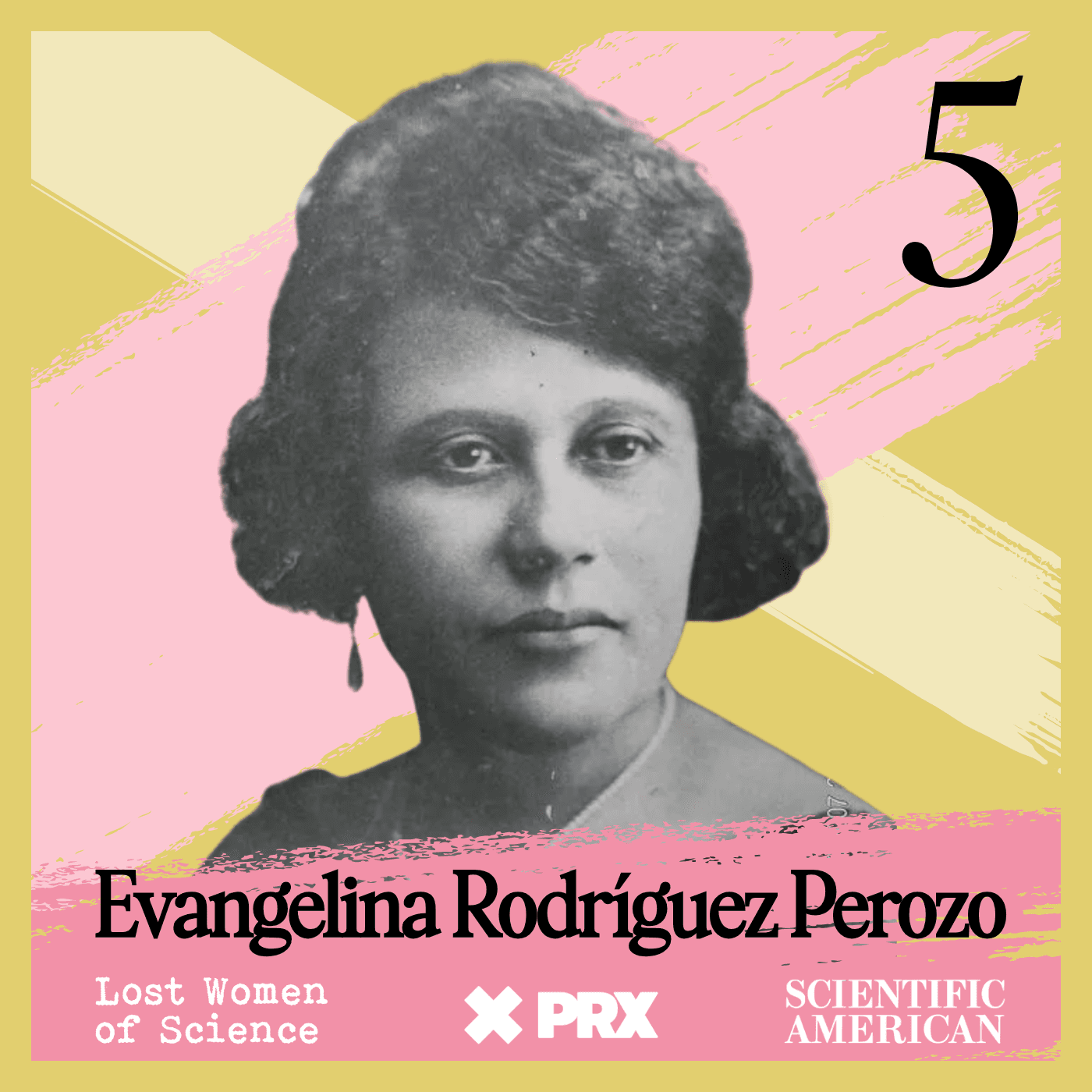

Lost Women of ScienceFor every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

For every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

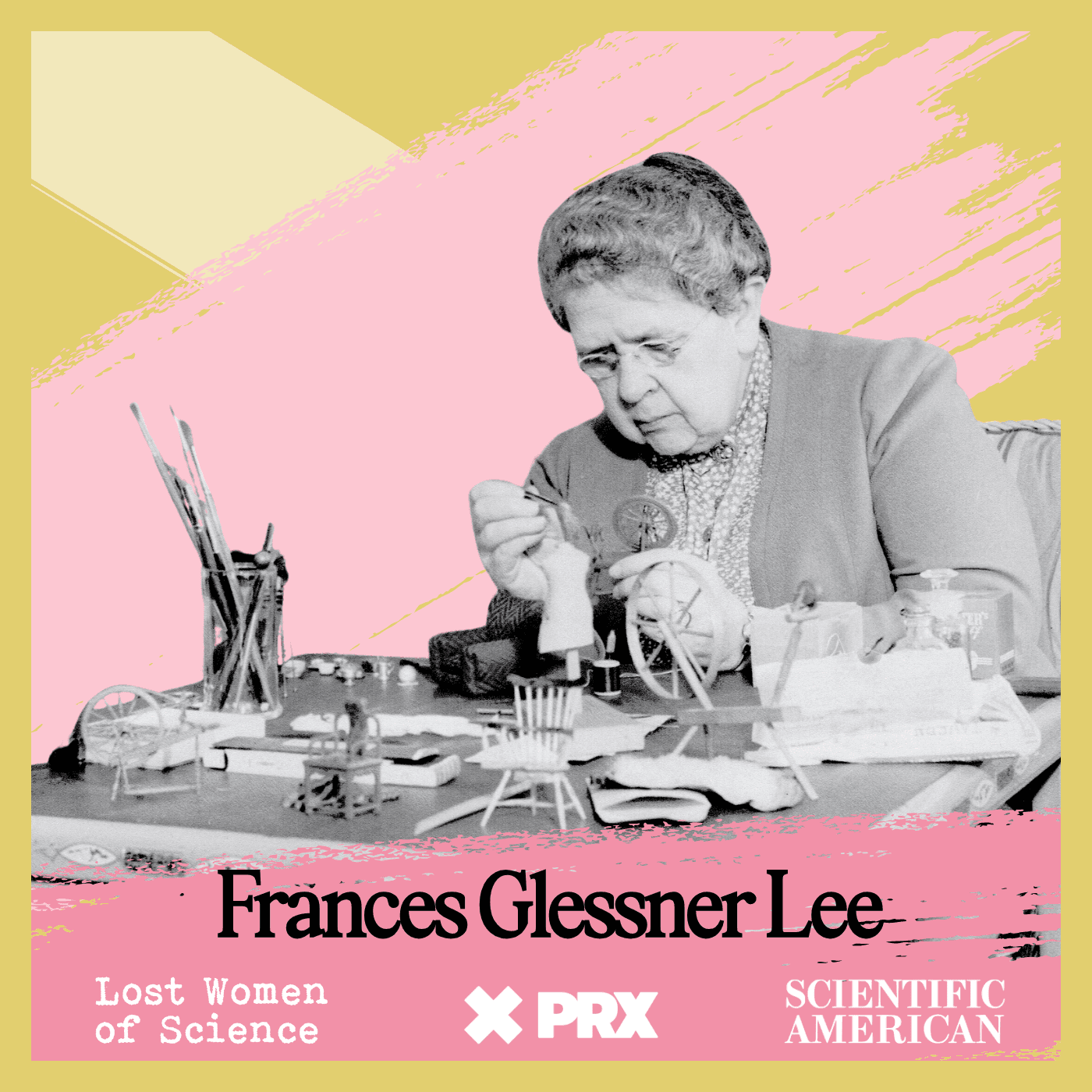

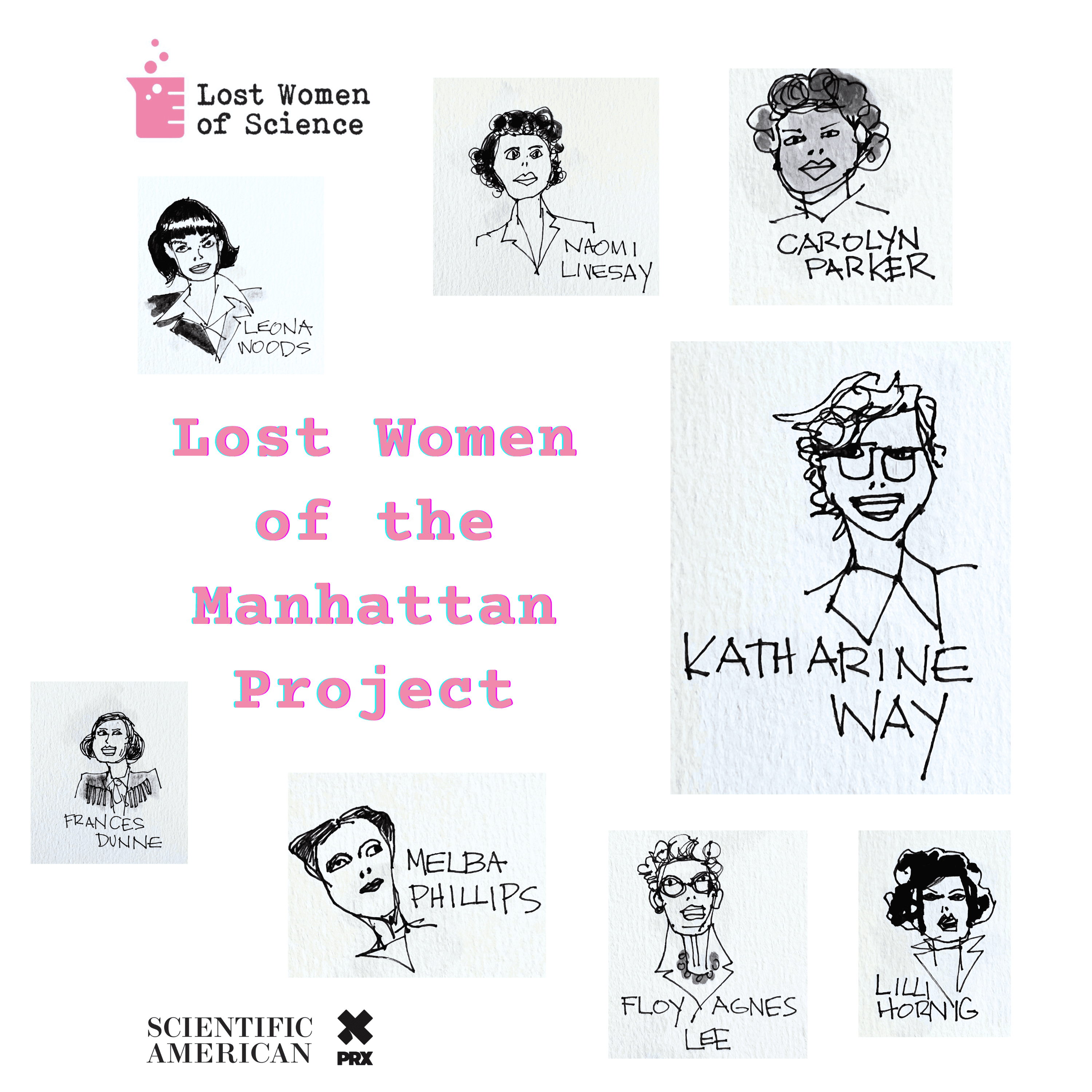

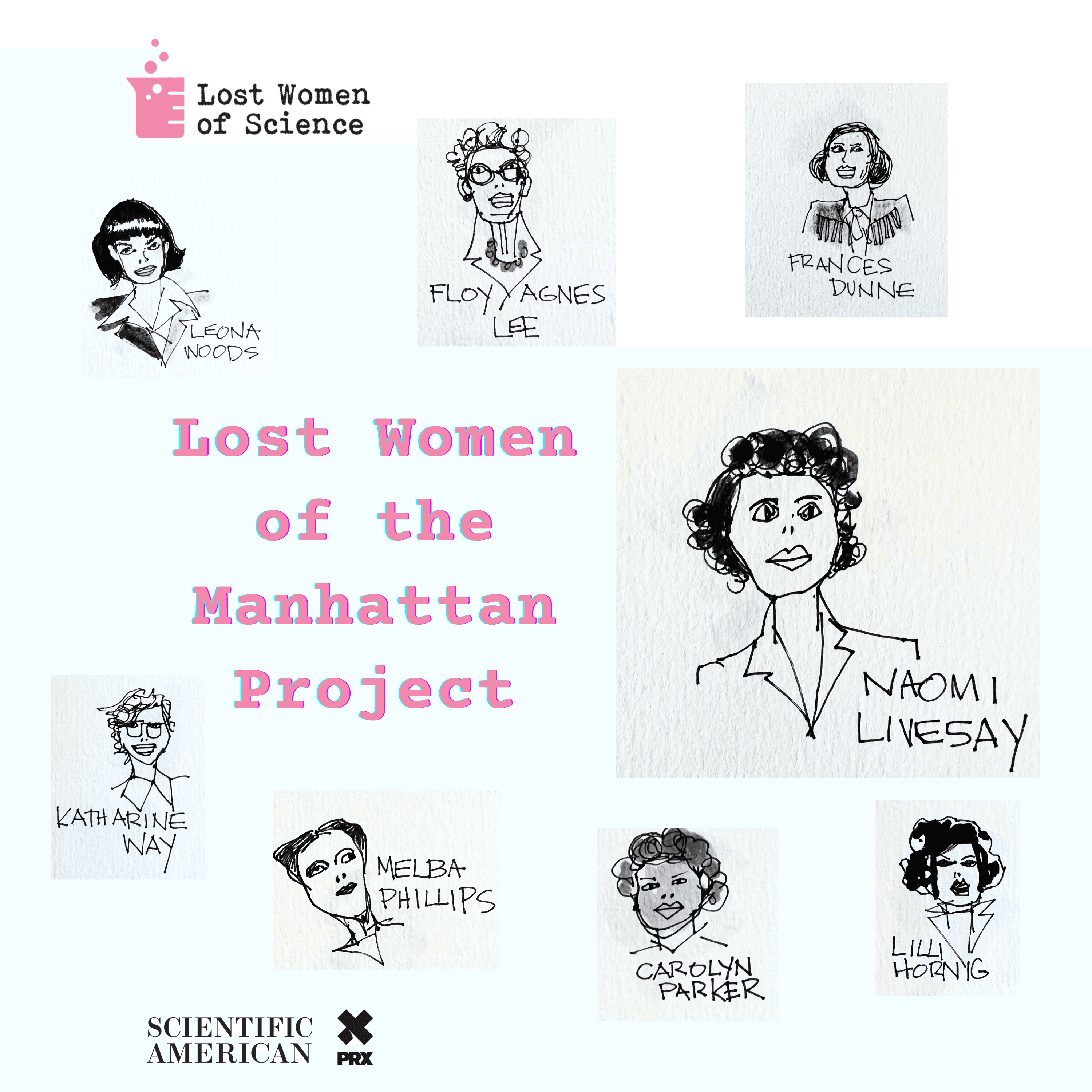

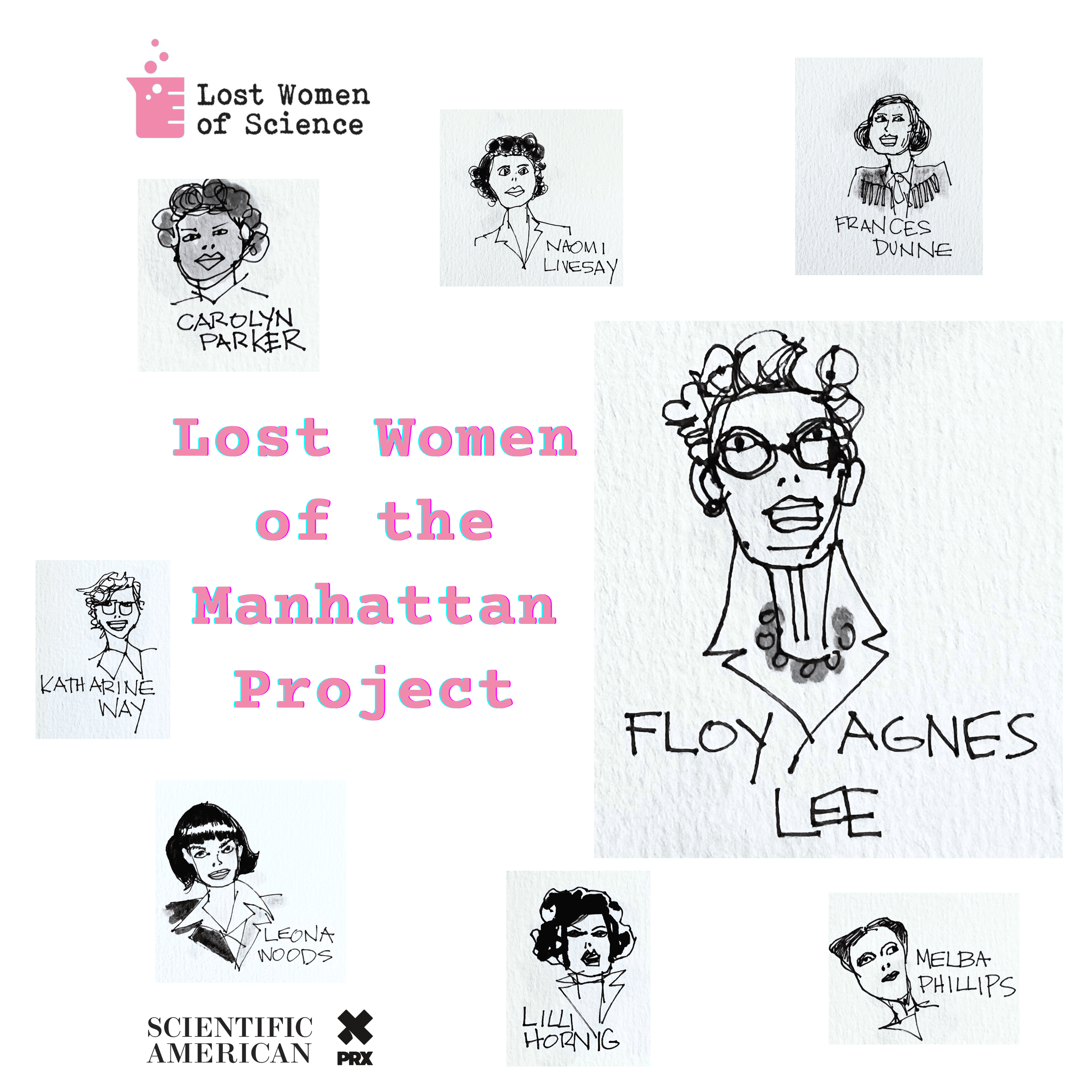

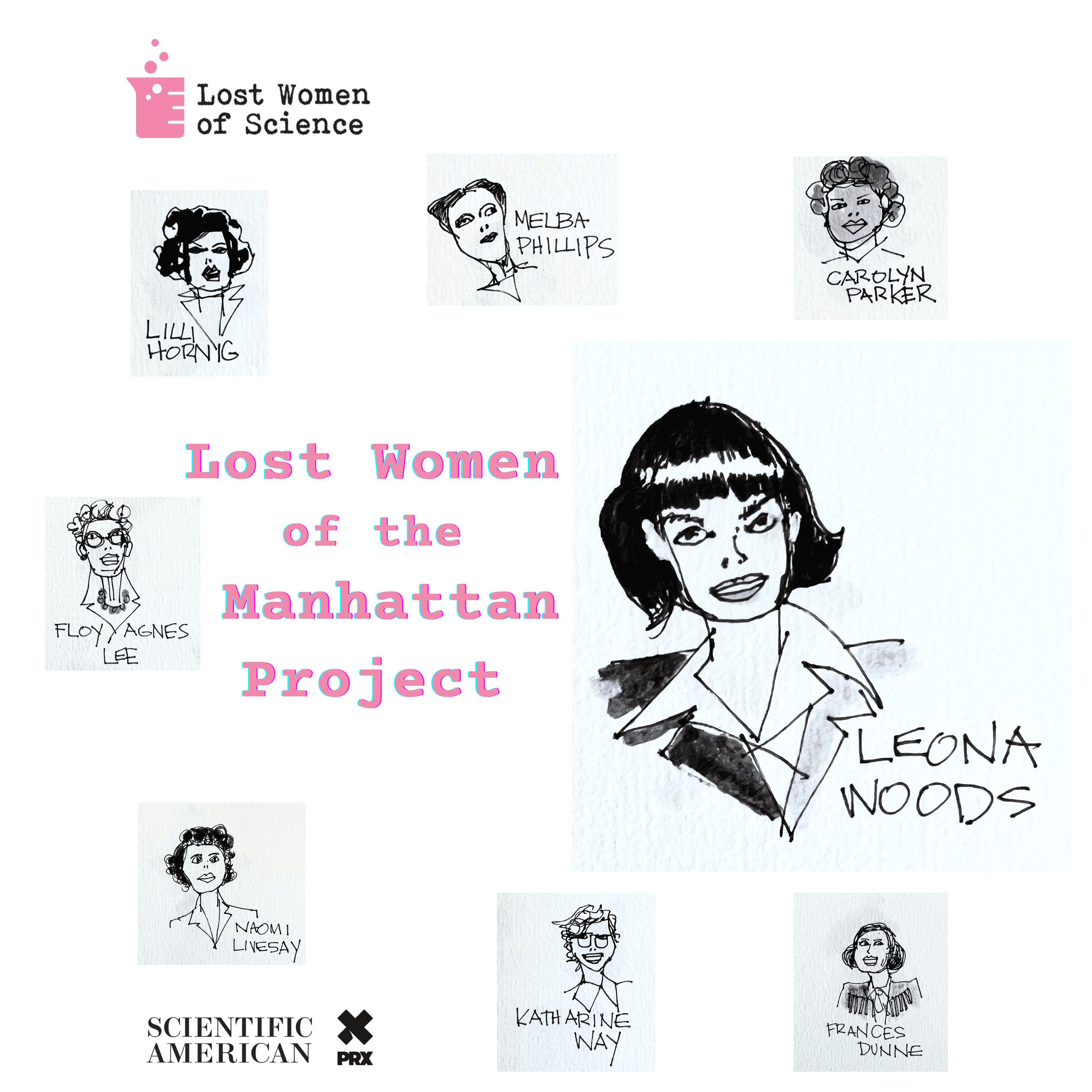

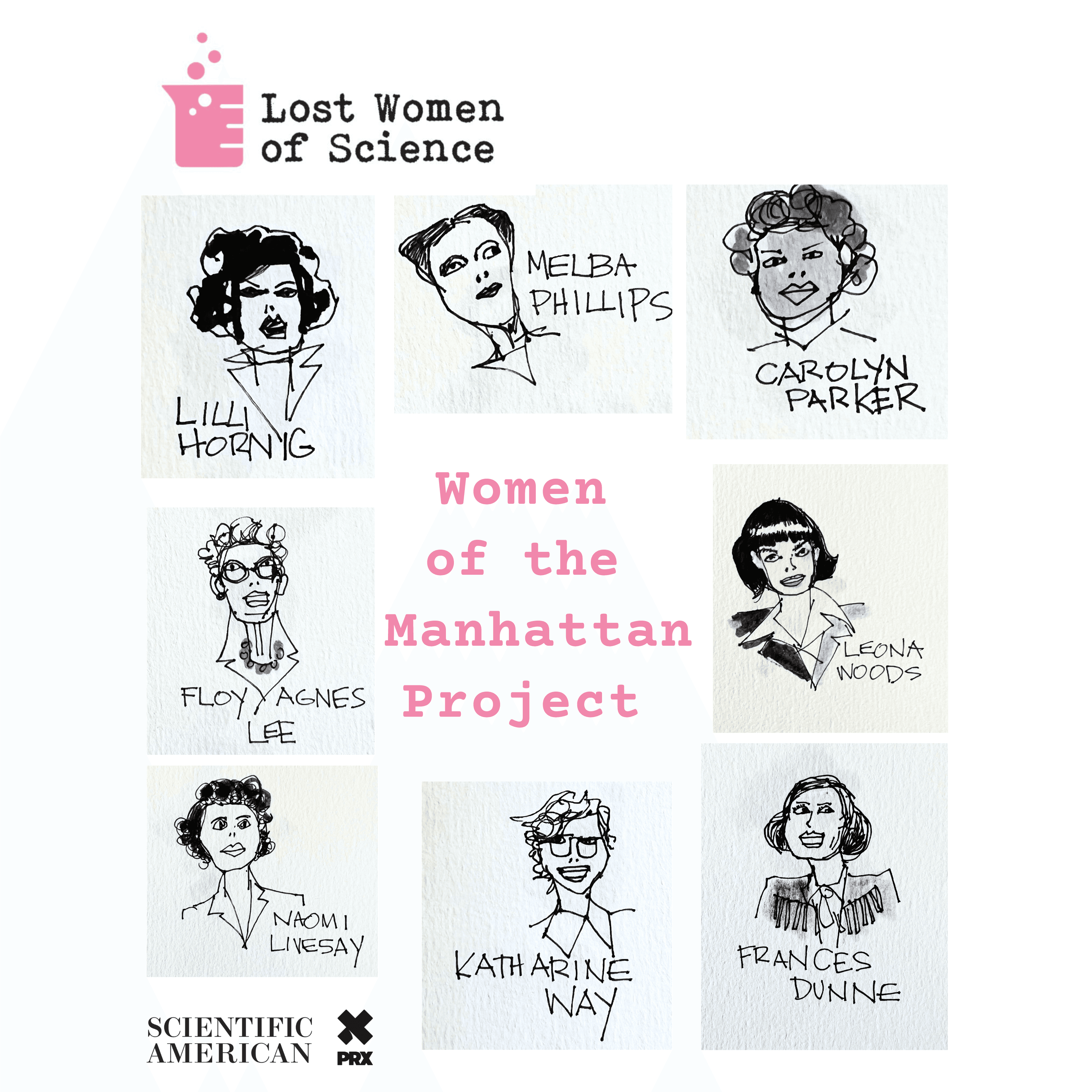

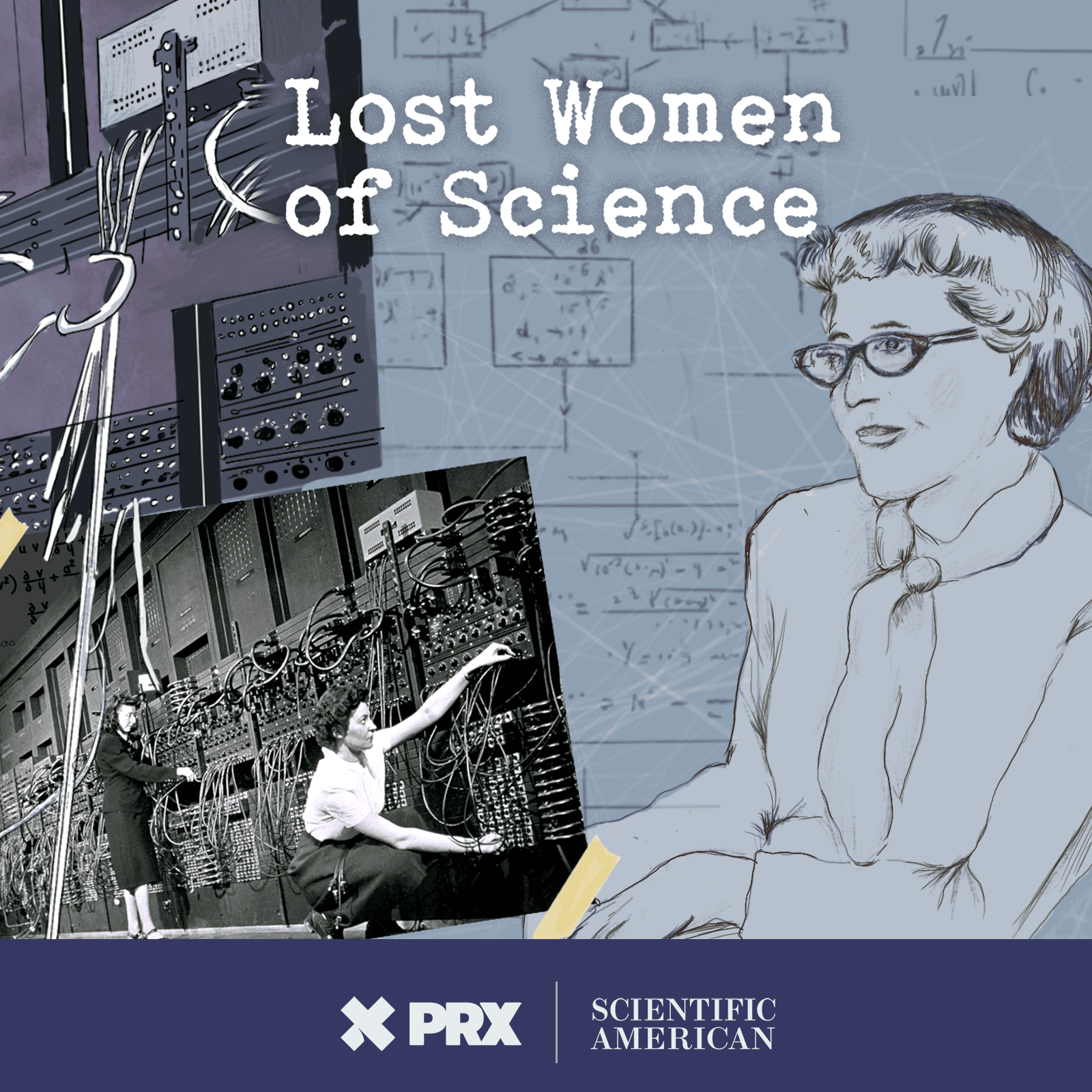

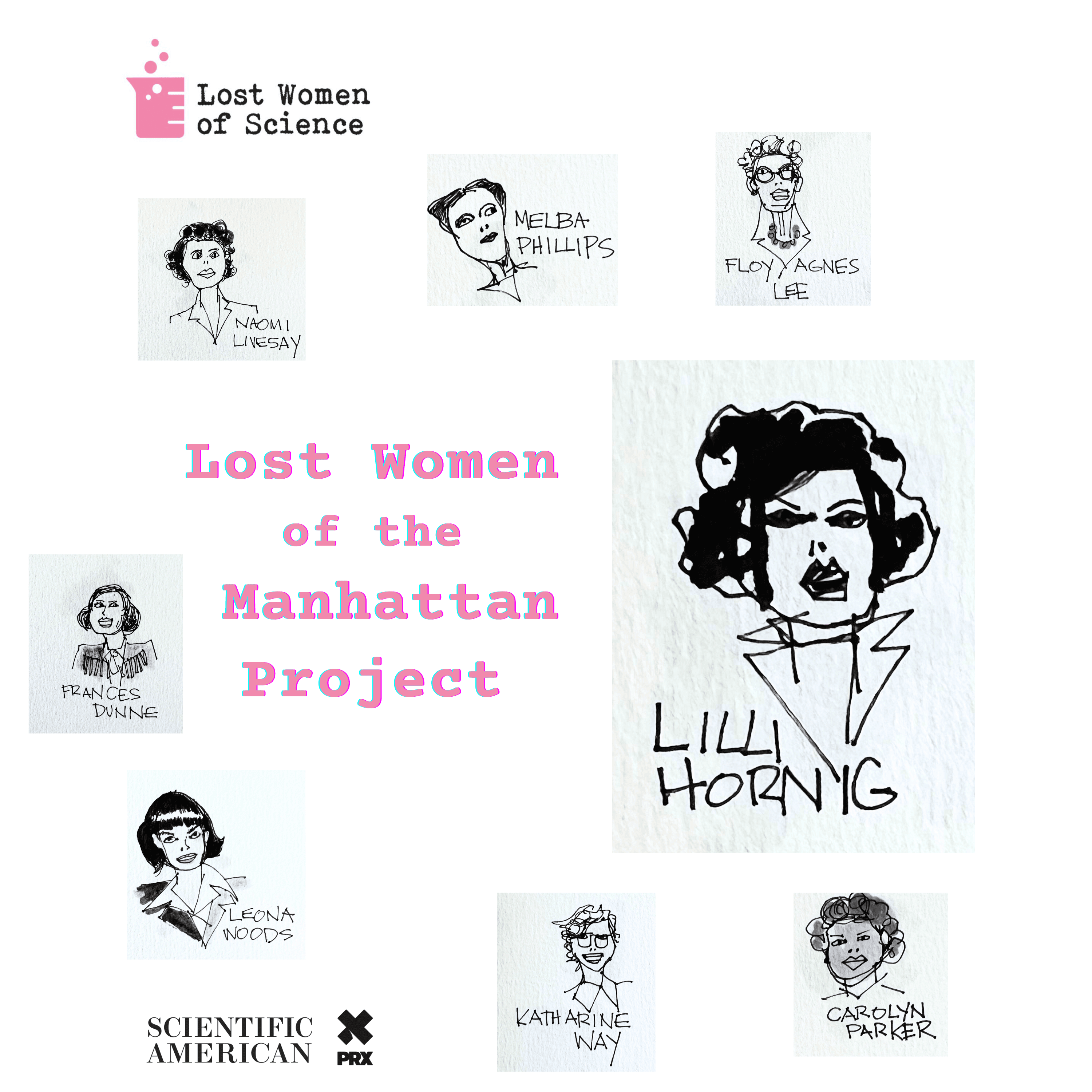

The Story of the Real Lilli Hornig, the Only Female Scientist Named in the Film Oppenheimer

Lilli Hornig was only 23 years old when she arrived at Los Alamos to contribute to the development of an atomic bomb that would end World War II. A talented chemist, Lilli battled sexism throughout her career and remained a steadfast advocate for female scientists like herself.

Lilli is the only female scientist named in Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer. But the character is a blur, popping up here and there to say they didn’t teach typing in her graduate chemistry program at Harvard, when asked whether she could be a typist, or to rib a colleague, telling him that her reproductive system was better protected from radiation than his. The real Hornig worked closely on plutonium research and was part of the team that developed and tested the mechanism for the plutonium weapon in the Trinity test.

Learn about your ad choices: dovetail.prx.org/ad-choices