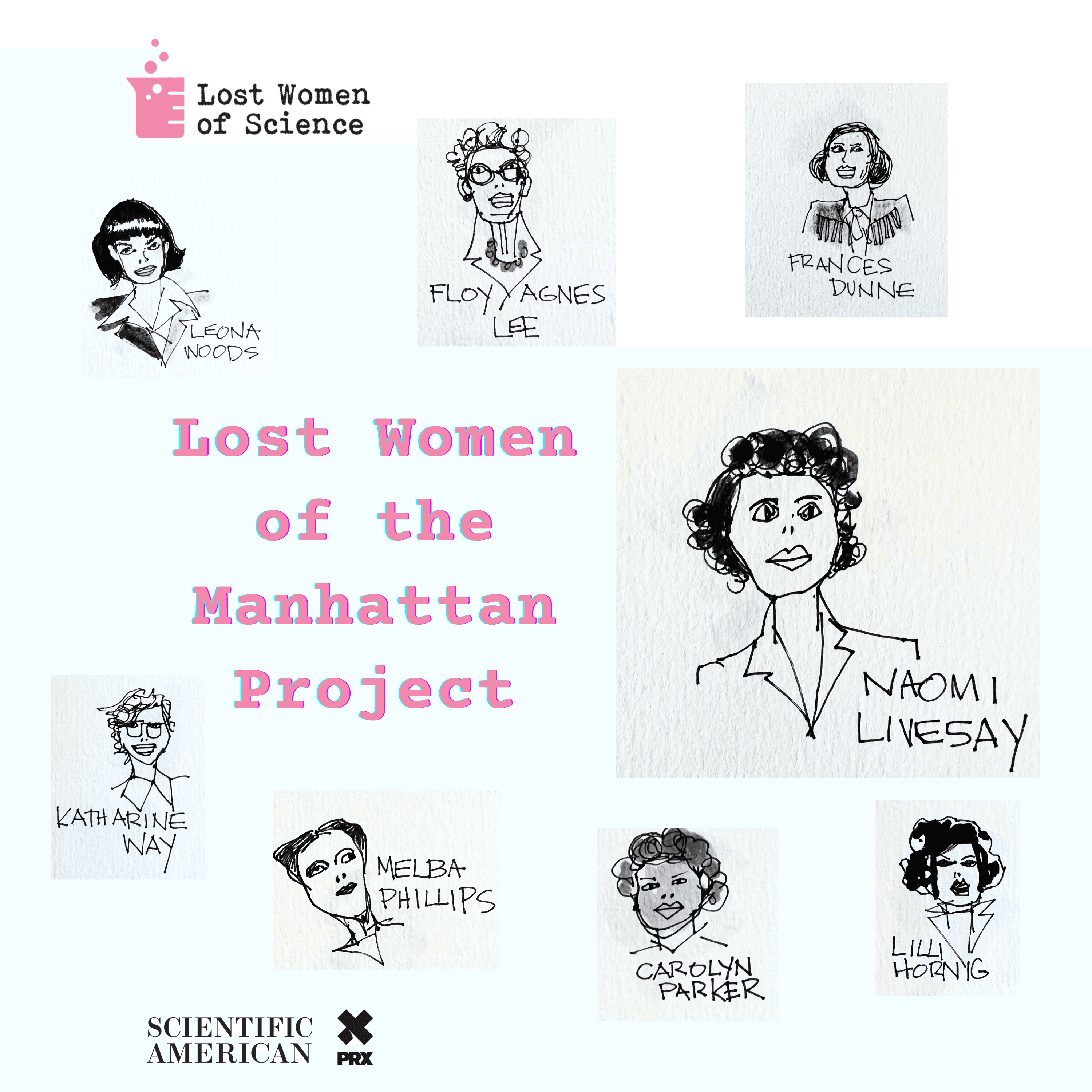

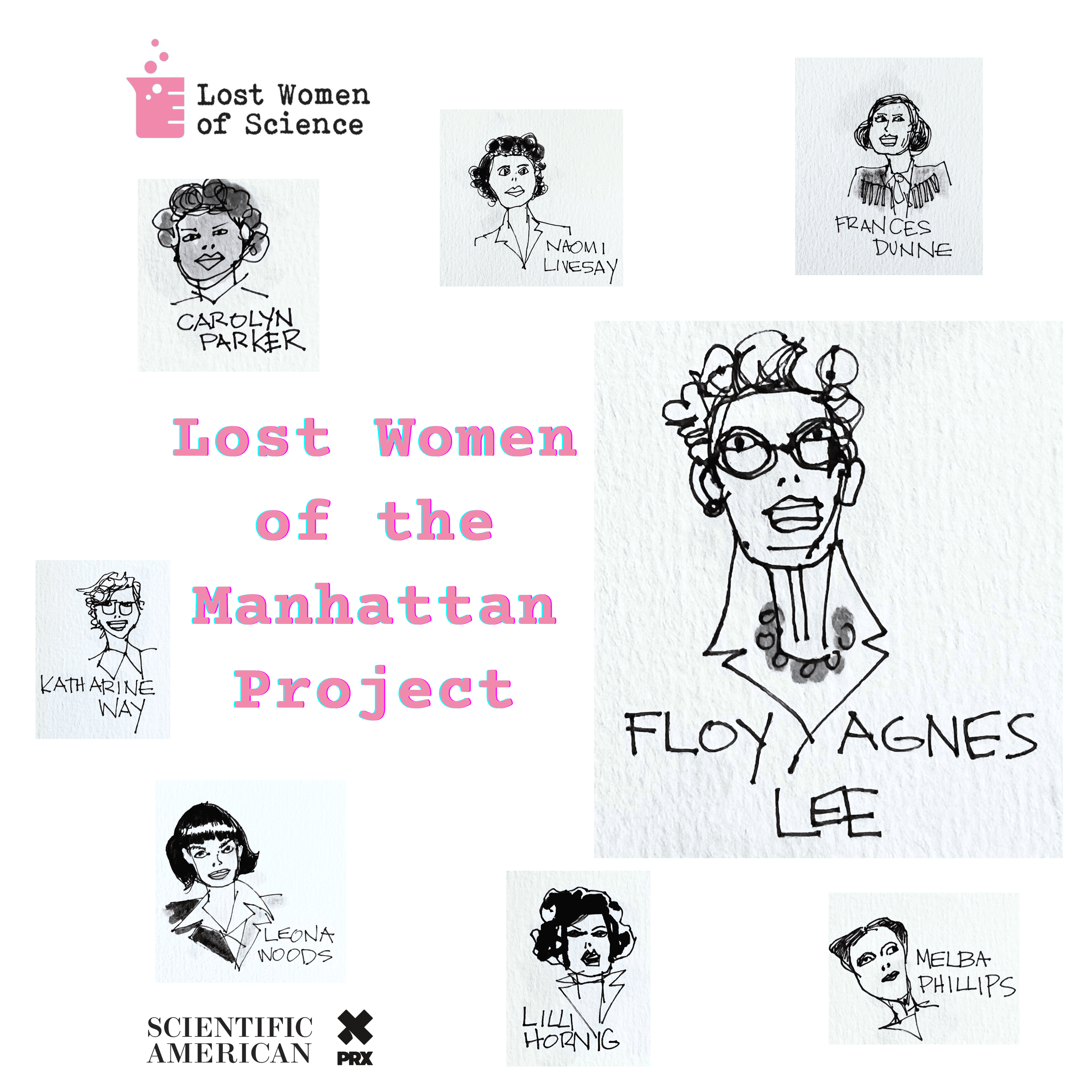

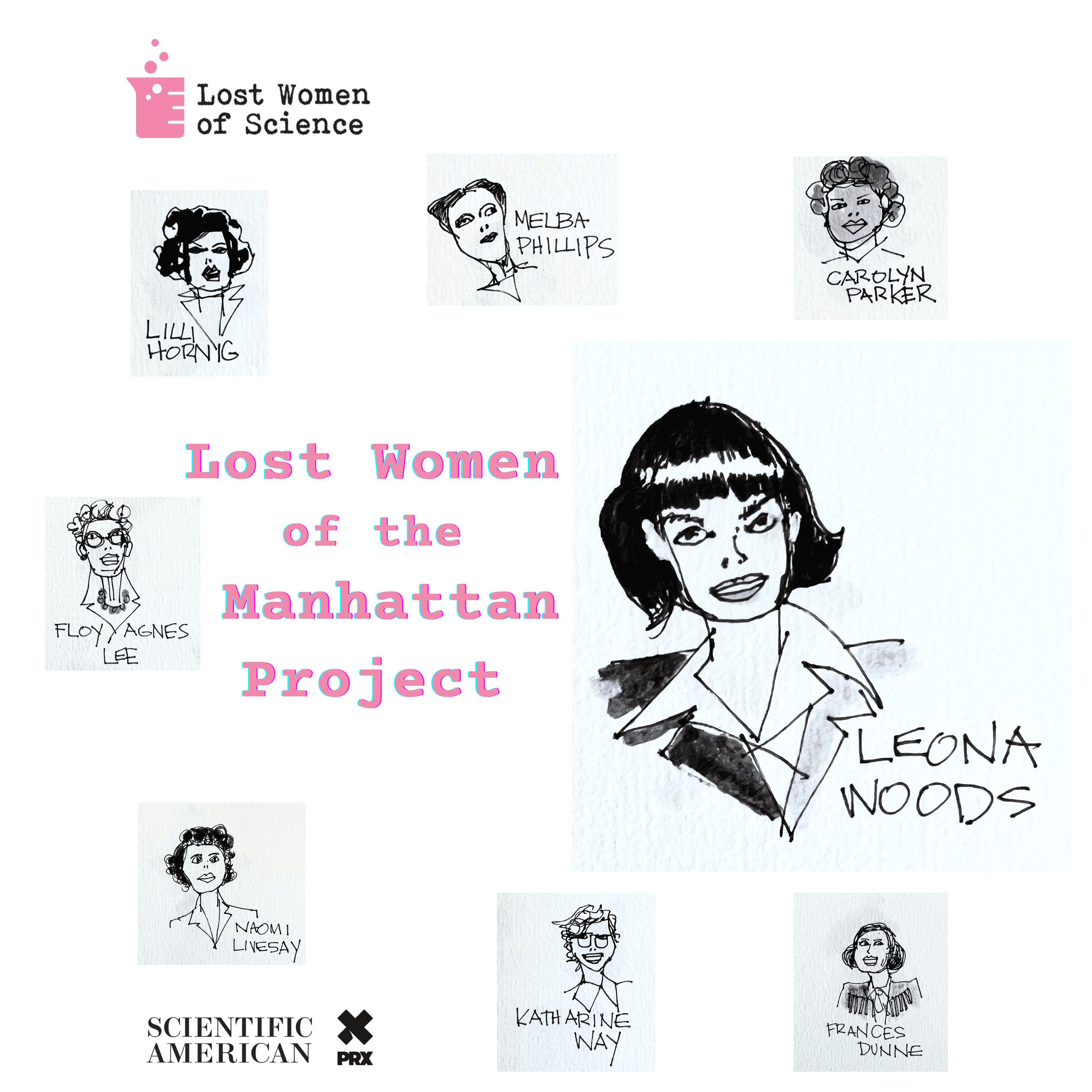

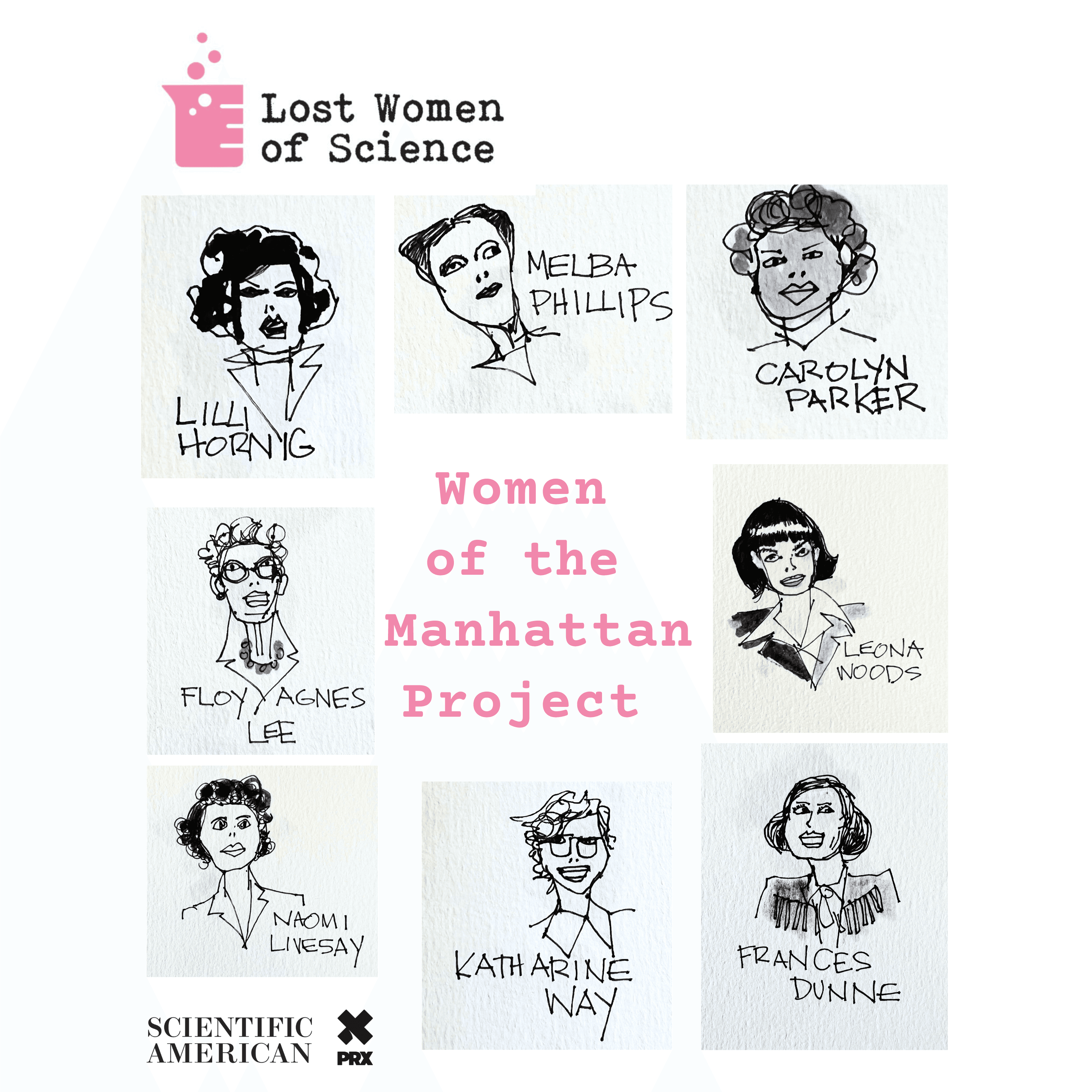

Lost Women of Science

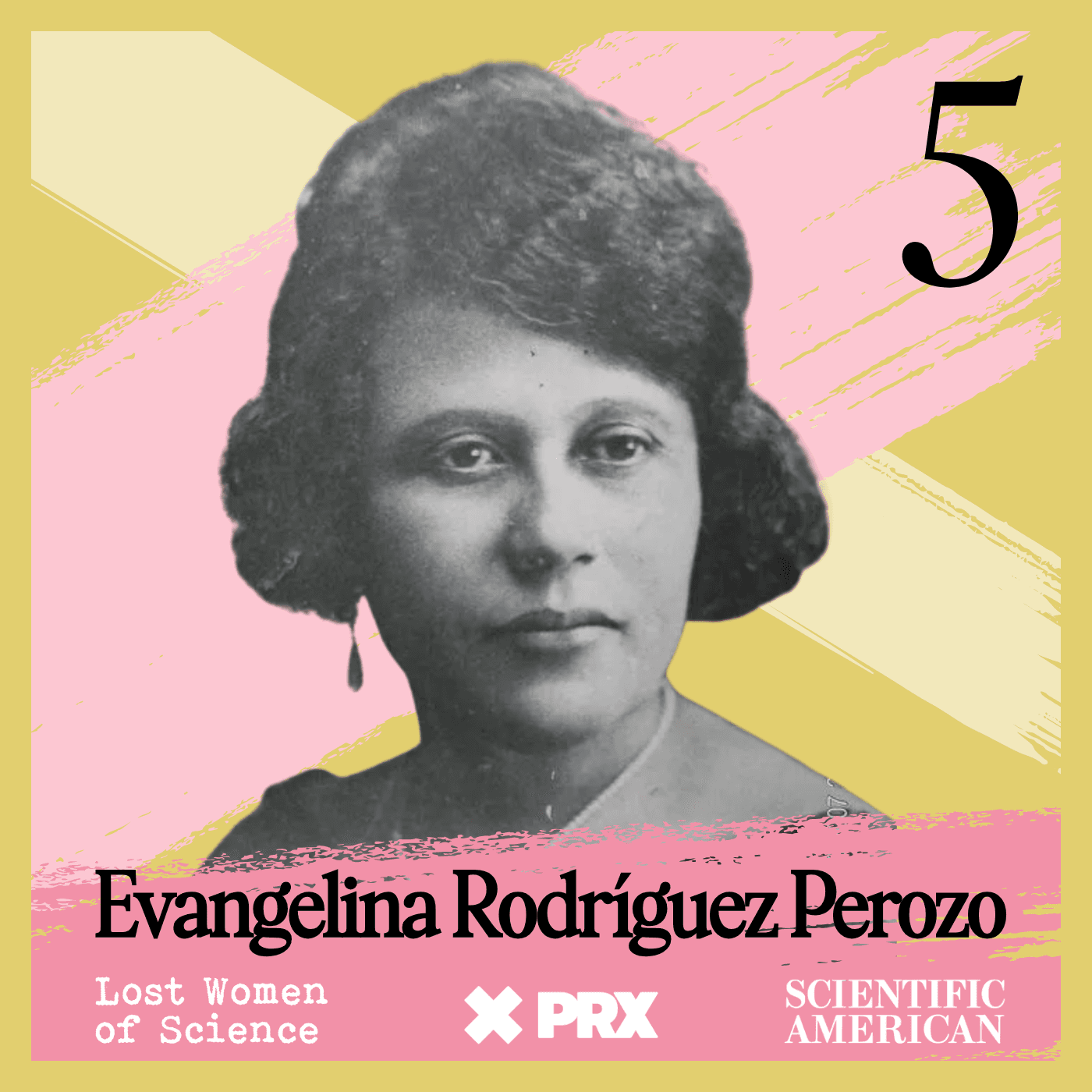

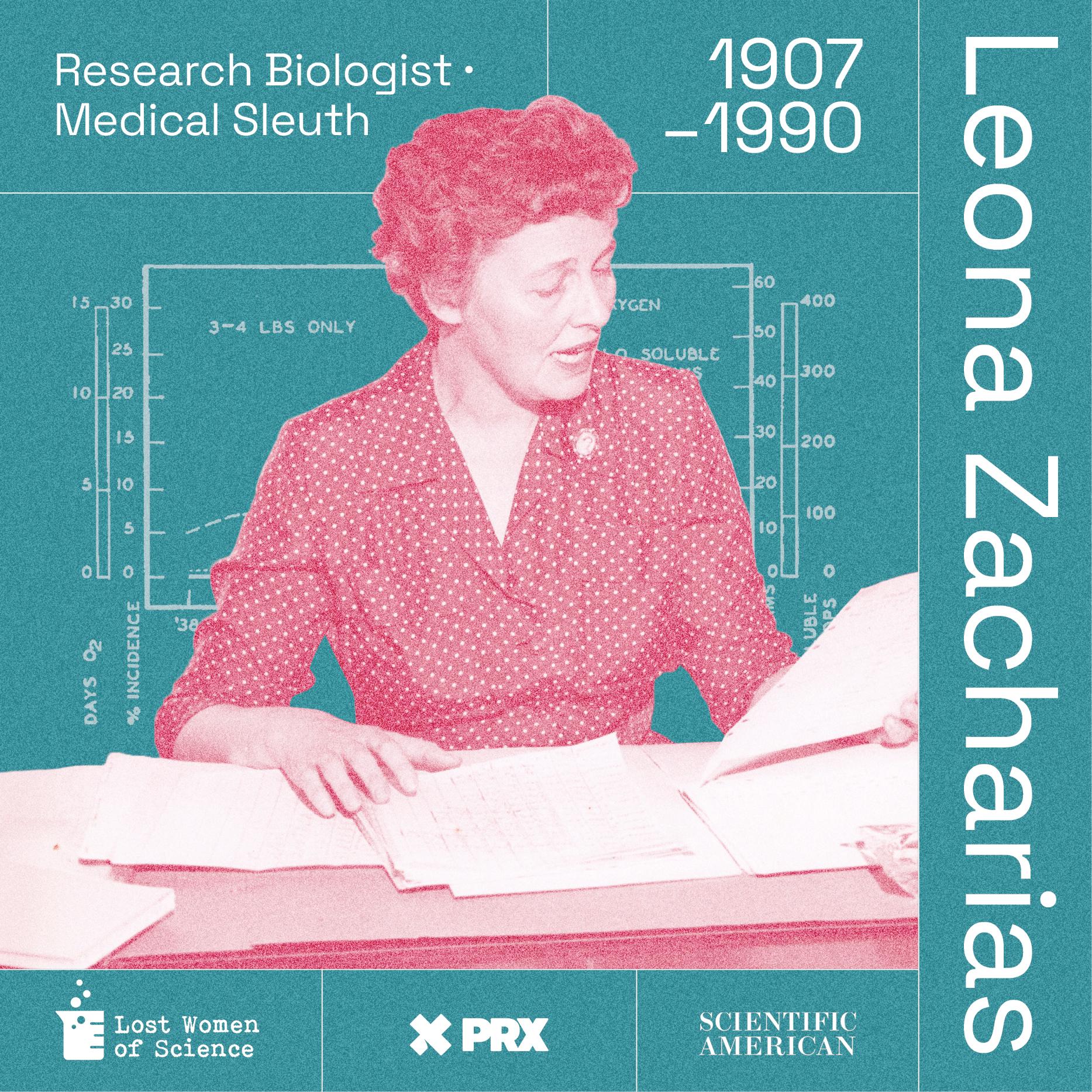

Lost Women of ScienceFor every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

For every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

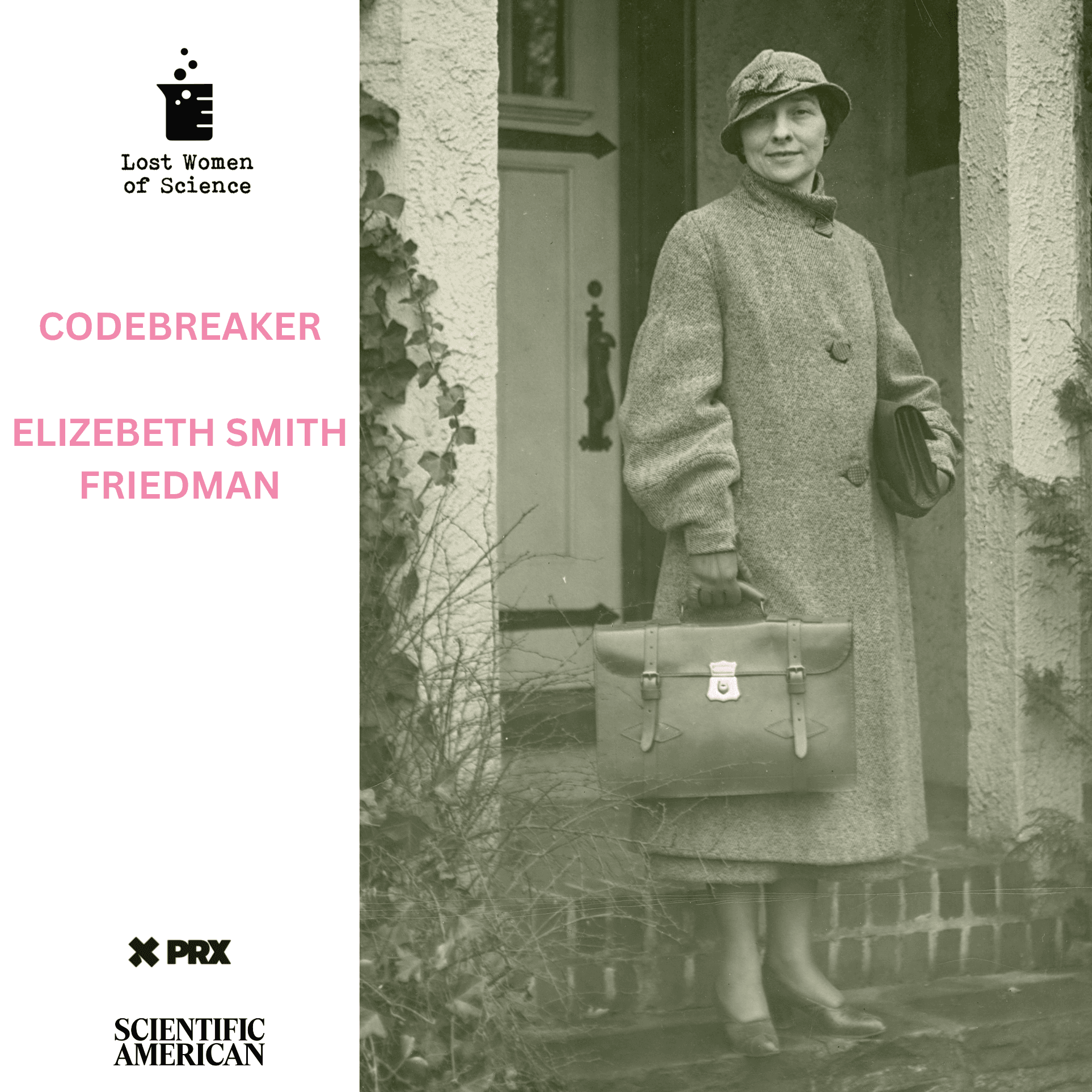

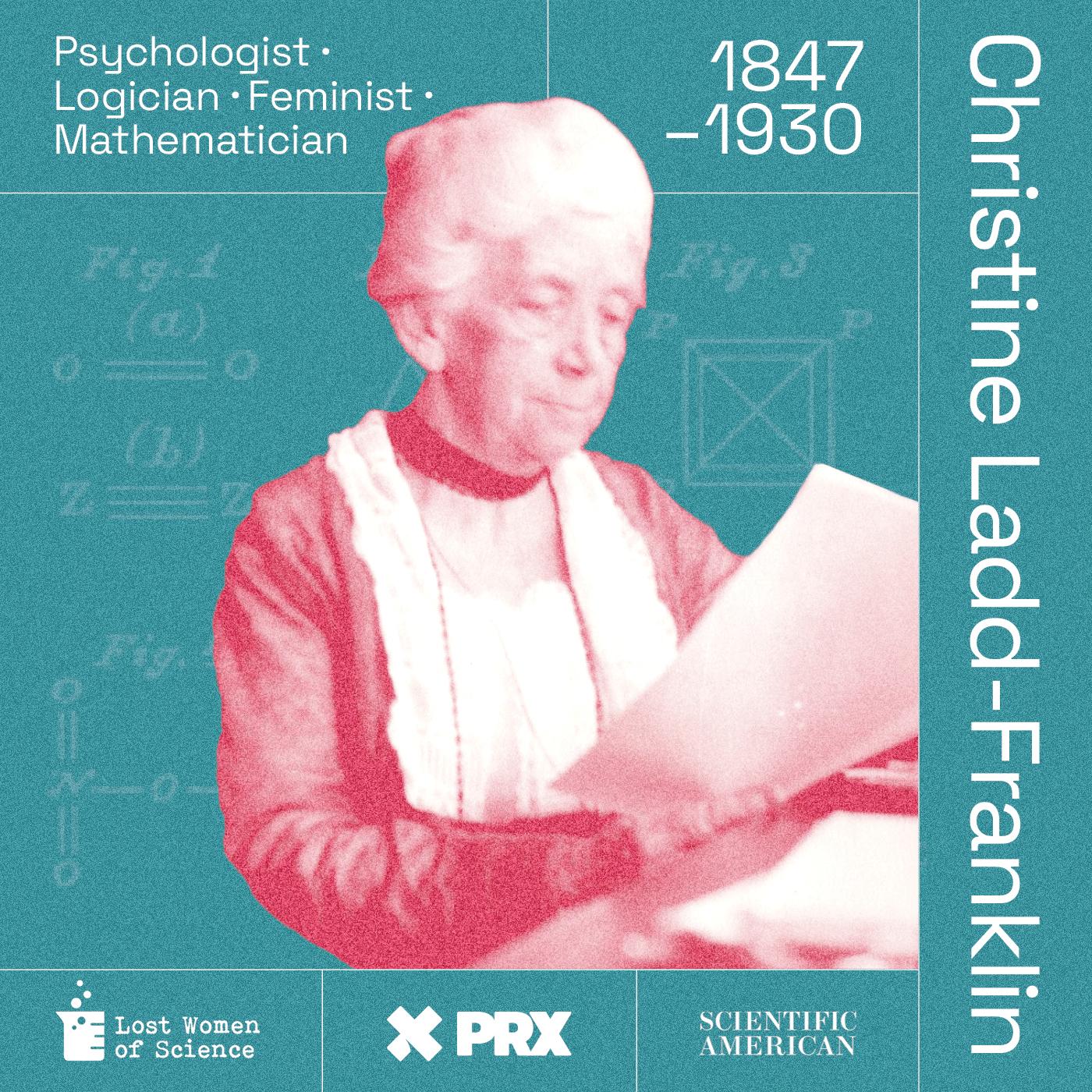

The Devastating Logic of Christine Ladd-Franklin

Christine Ladd-Franklin is best known for her theory of the evolution of color vision, but her research spanned math, symbolic logic, philosophy, biology, and psychology. Born in Connecticut in 1847, she was clever, sharp-tongued, and never shied away from a battle of wits. When she decided to go to college instead of pursuing a marriage, she convinced her skeptical grandmother by pointing to statistics: there was an excess of women in New England, so a husband would be hard to find; she’d better get an education instead. “Grandma succumbed,” she wrote in her diary. When a man didn't give her credit for her “antilogism,” the core construct in her system of deductive reasoning, she took him to task in print, taking time to praise the beauty of her own concepts. And when Johns Hopkins University attempted to grant Ladd-Franklin an honorary PhD in 1926, she insisted that they grant her the one she'd already earned — after all, she’d completed her dissertation there, without official recognition, more than 40 years earlier. Johns Hopkins succumbed.

Learn about your ad choices: dovetail.prx.org/ad-choices