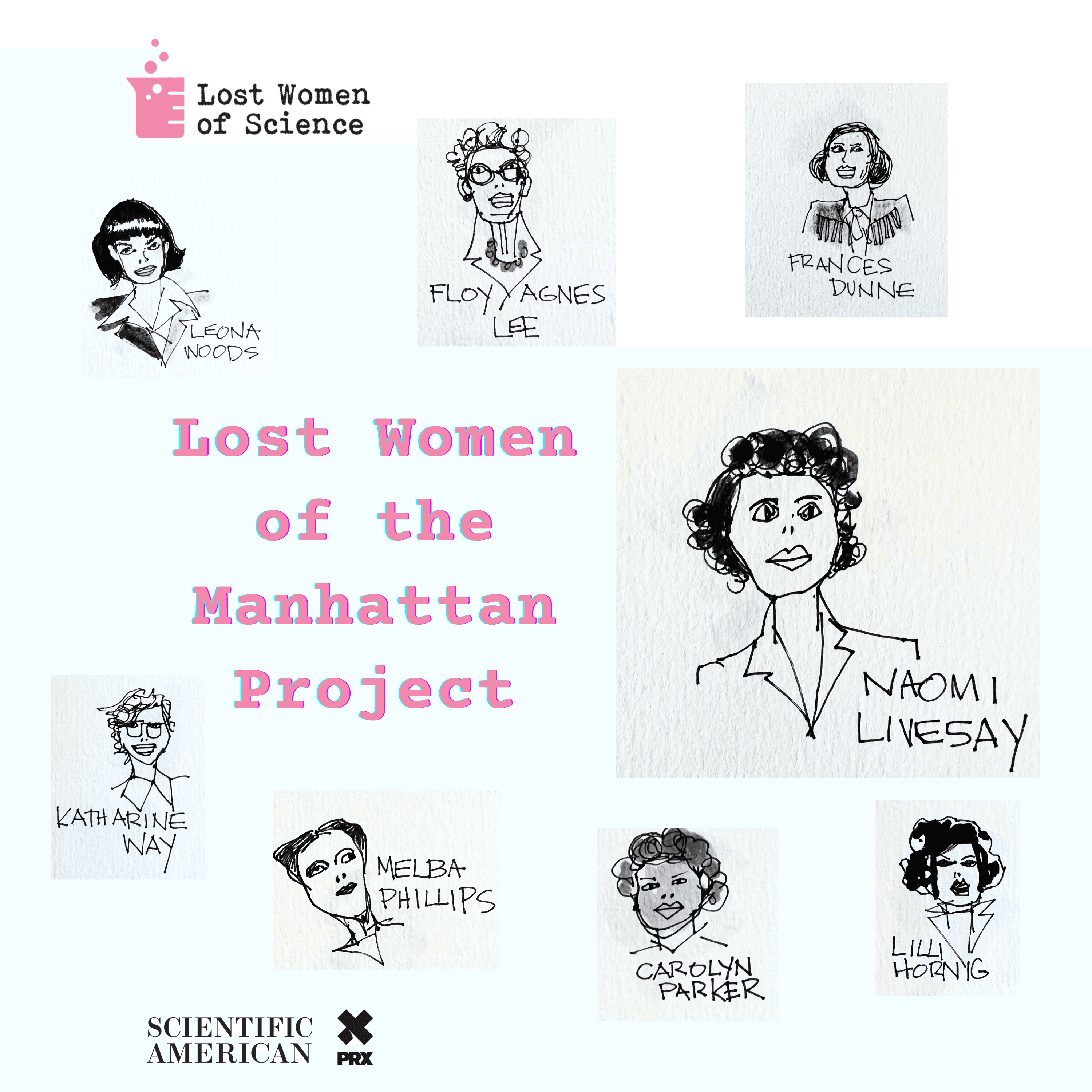

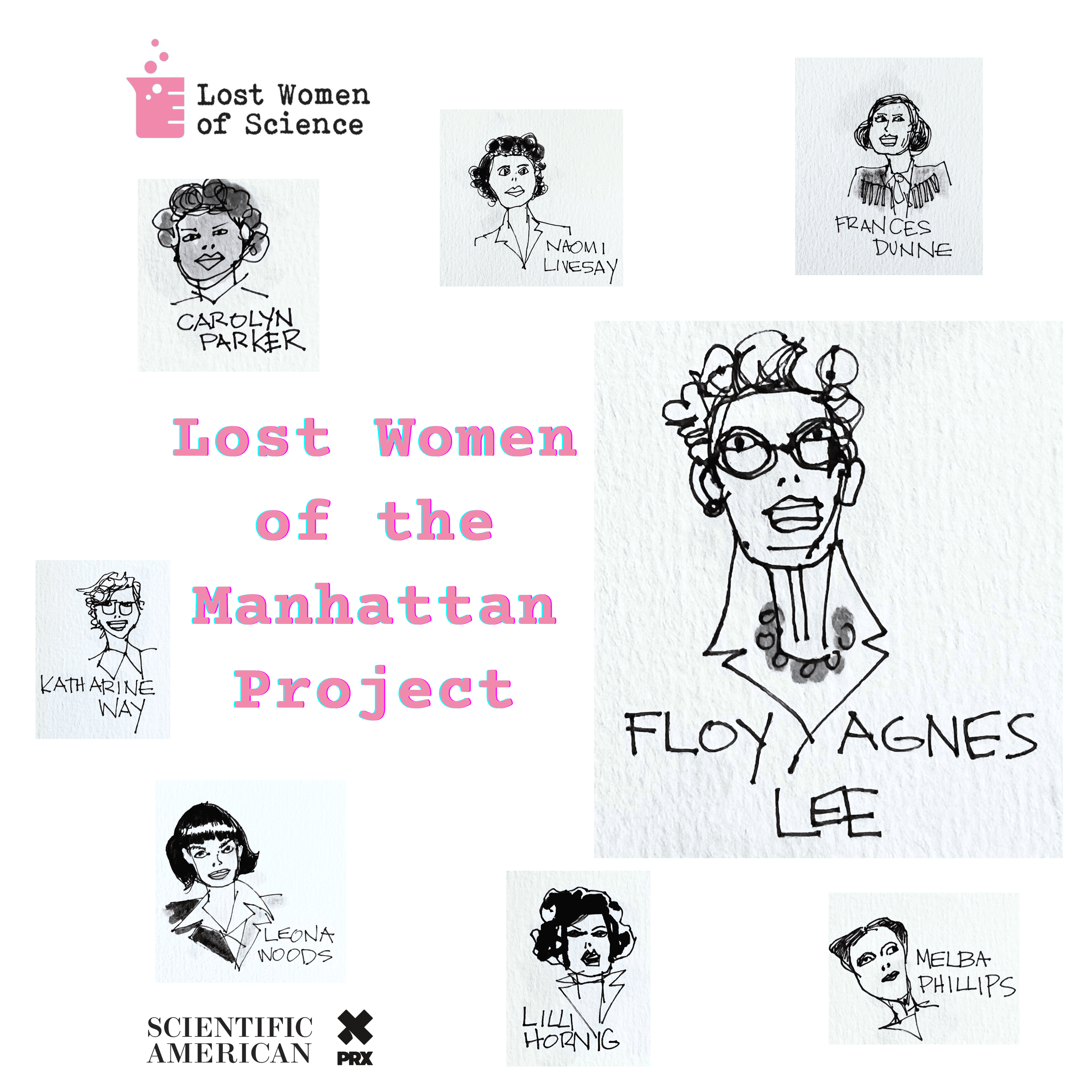

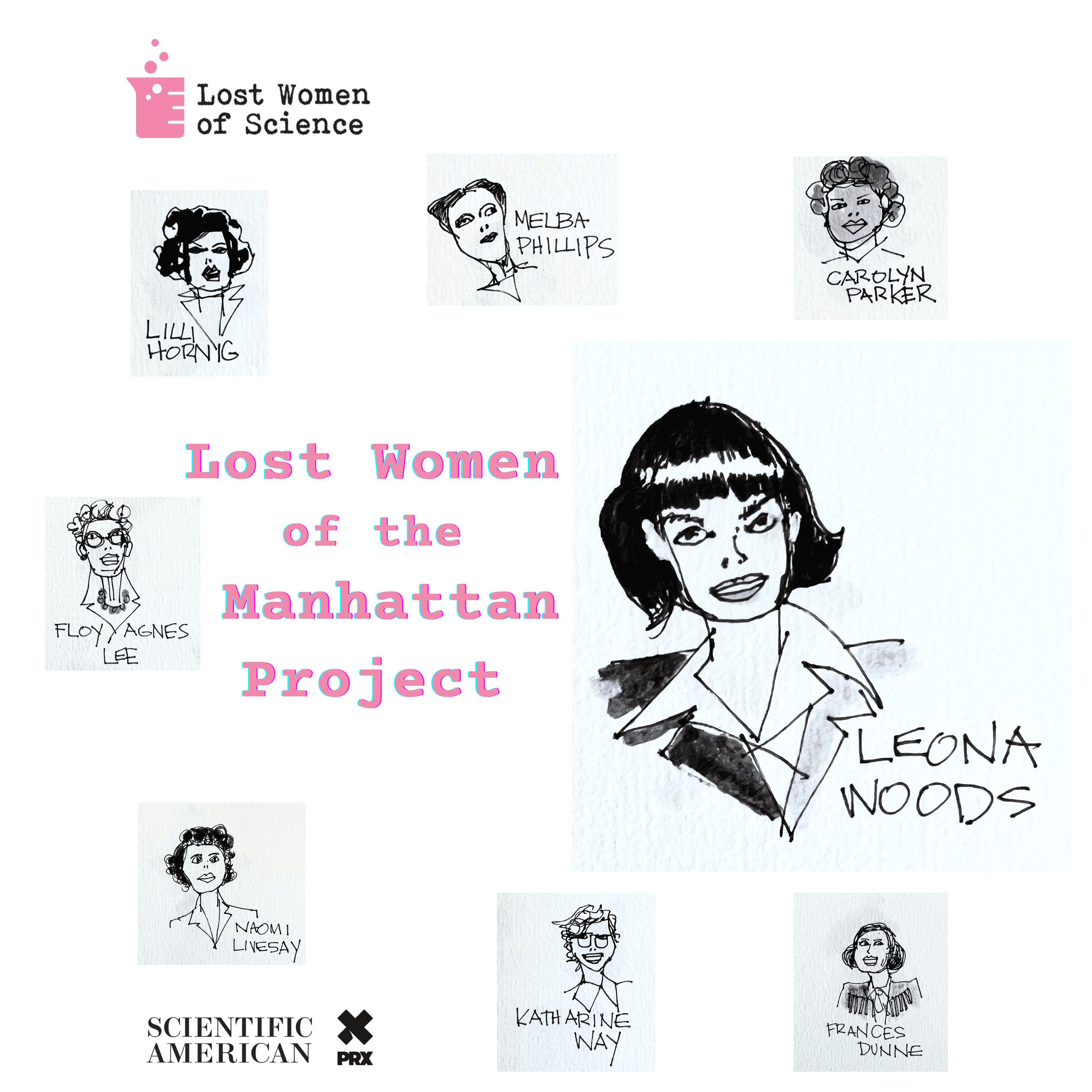

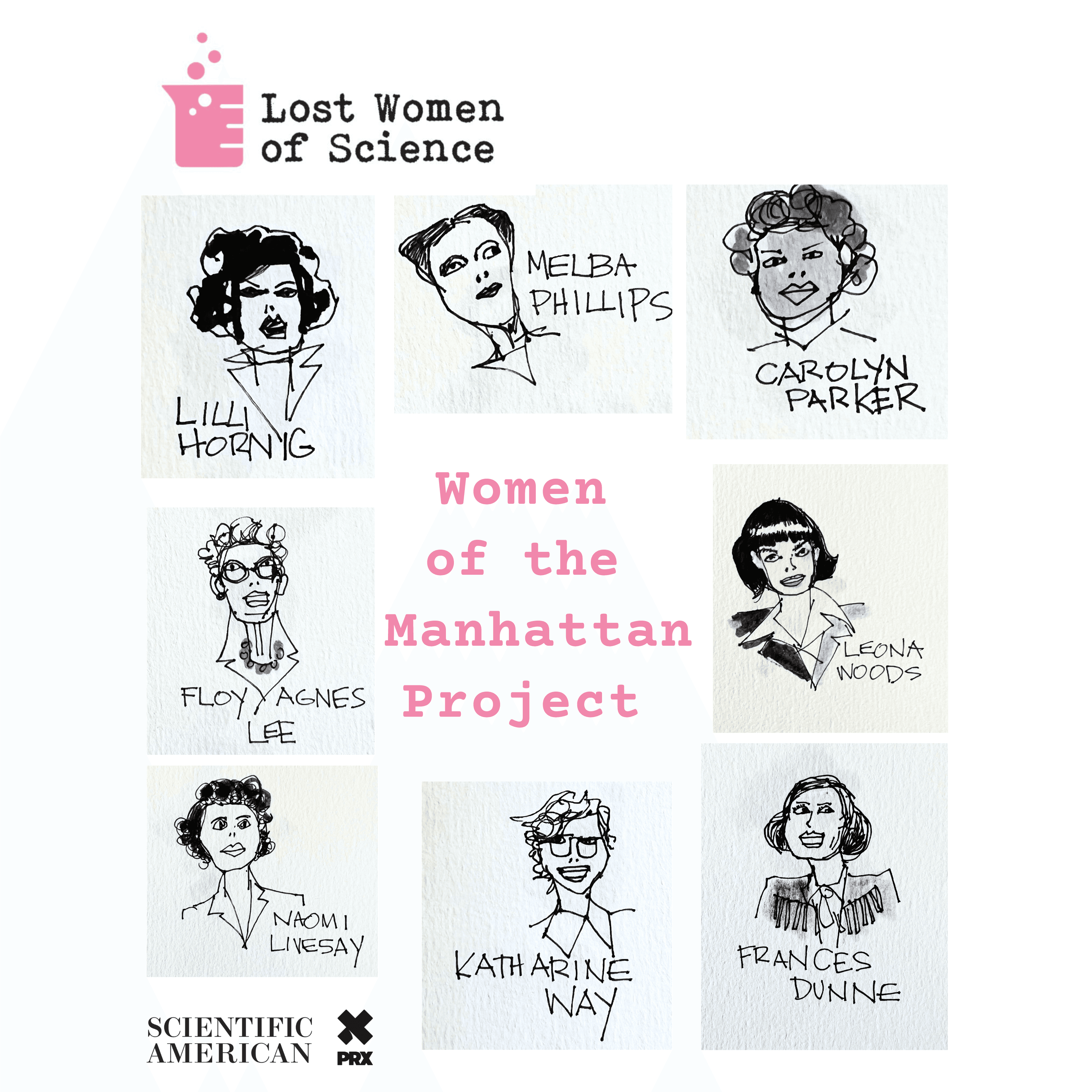

Lost Women of Science

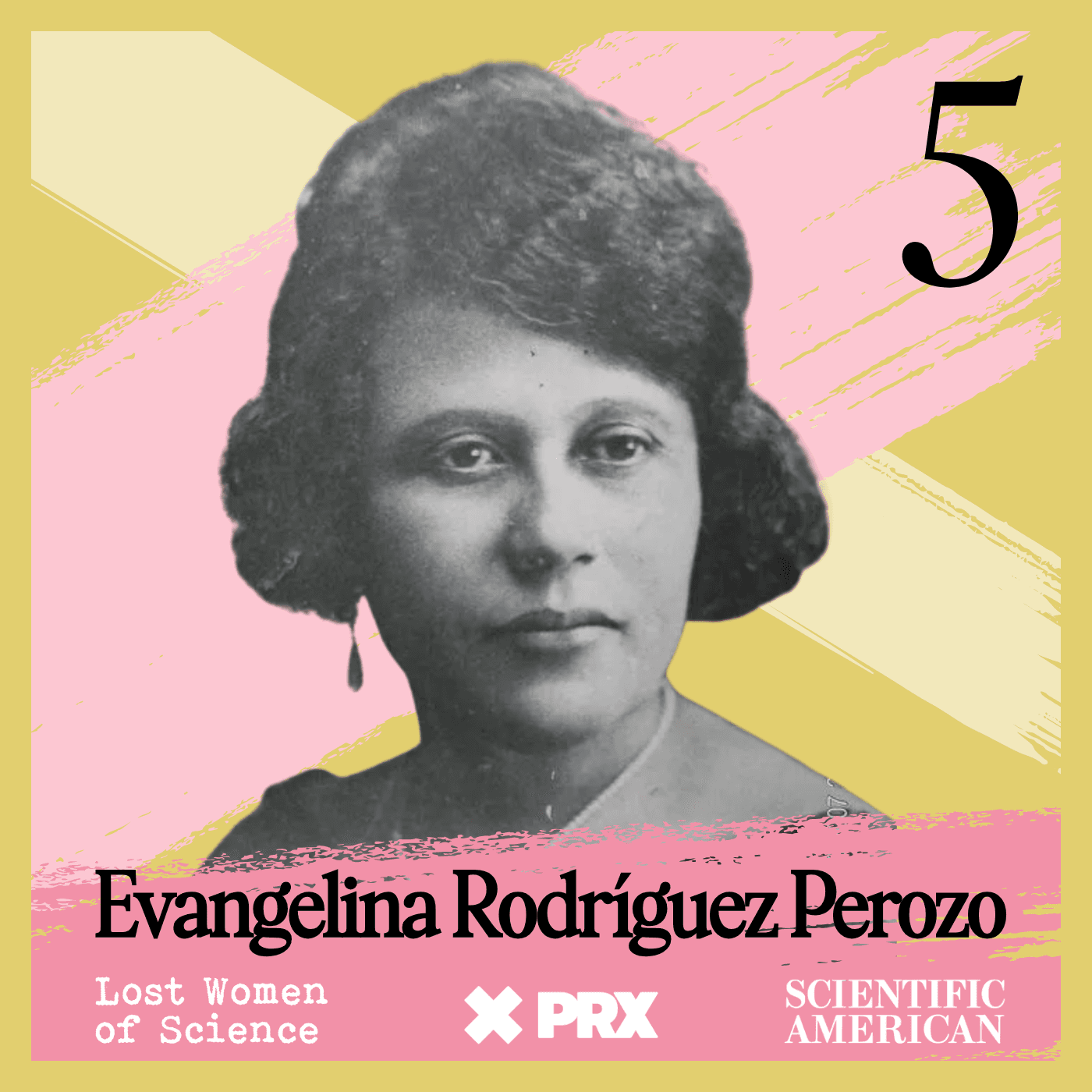

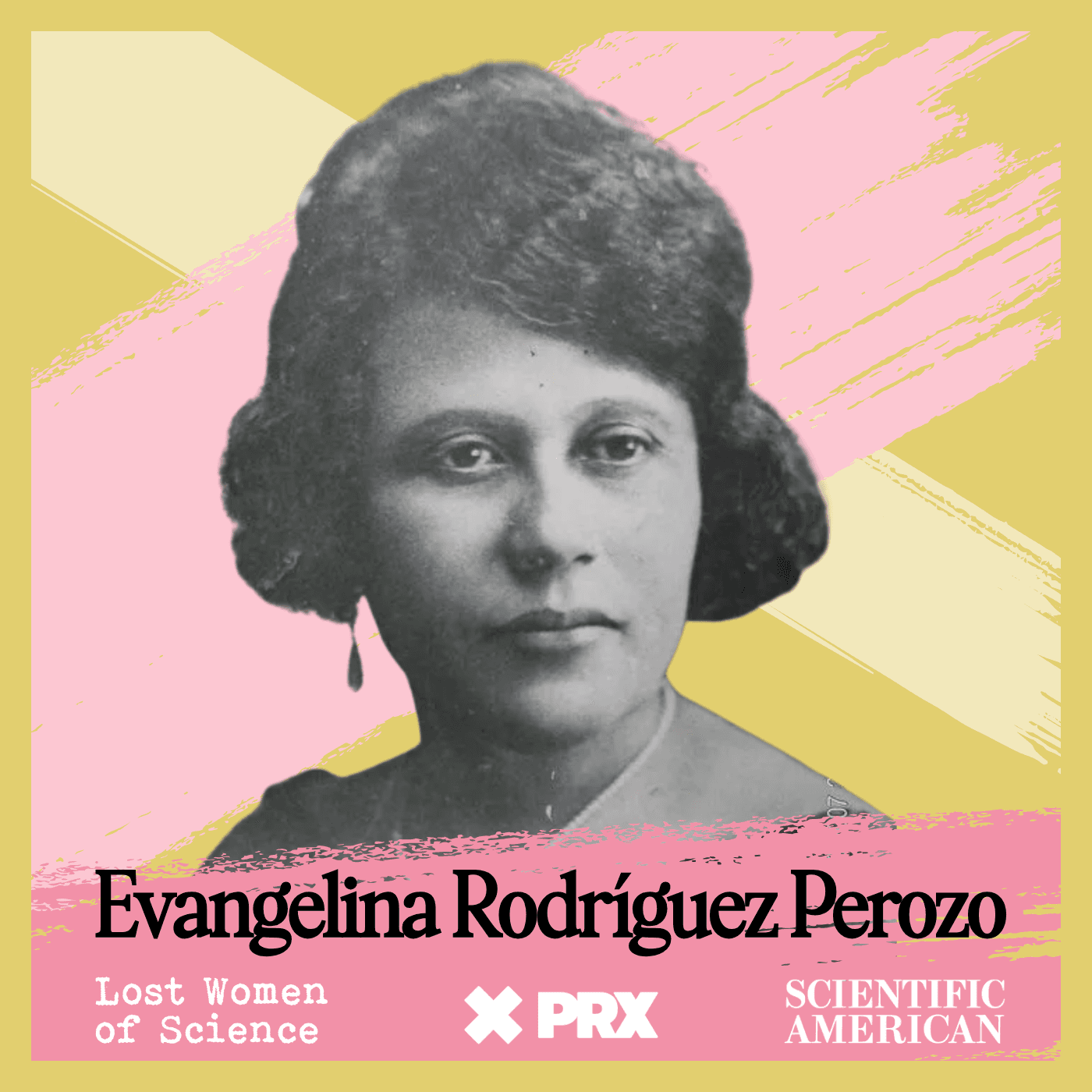

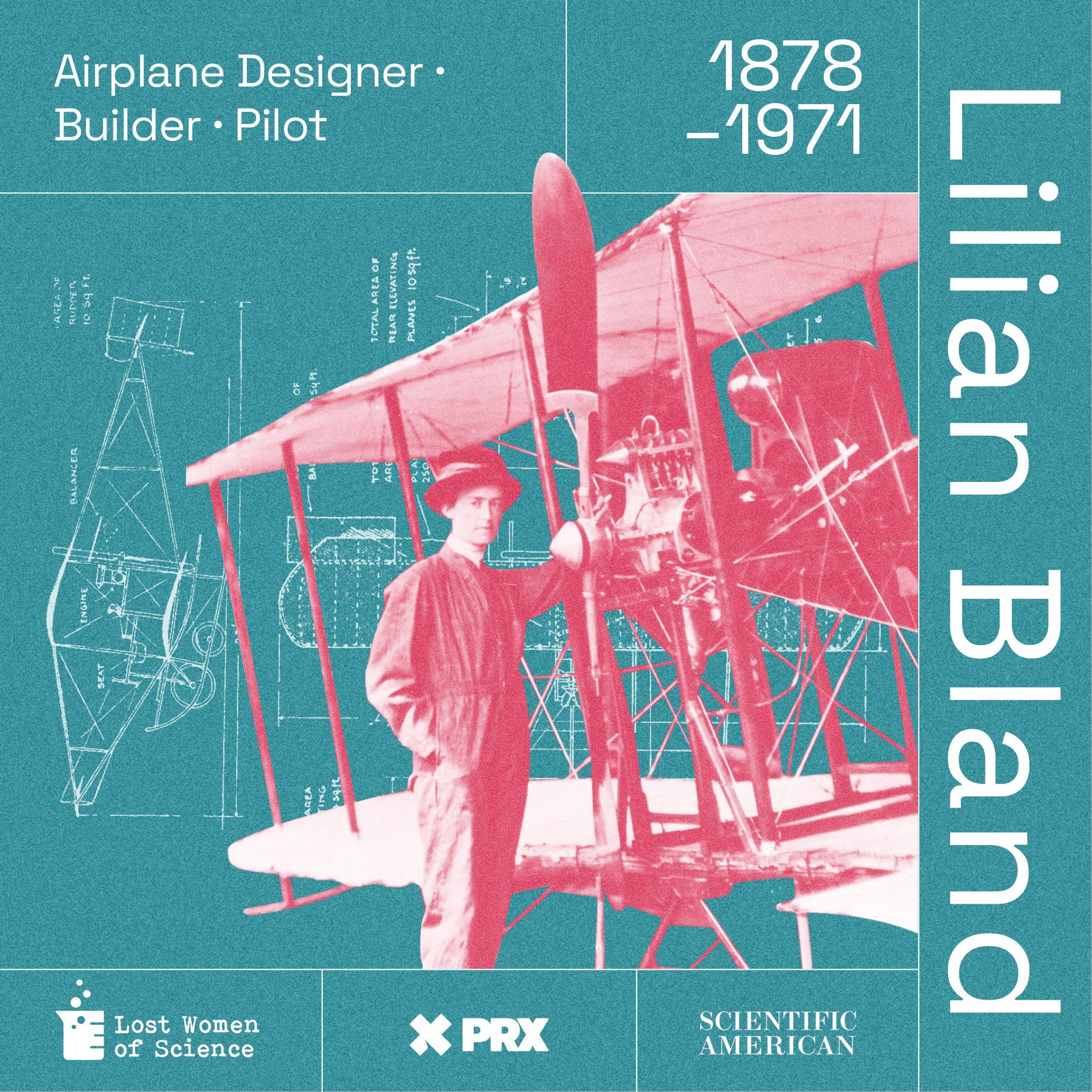

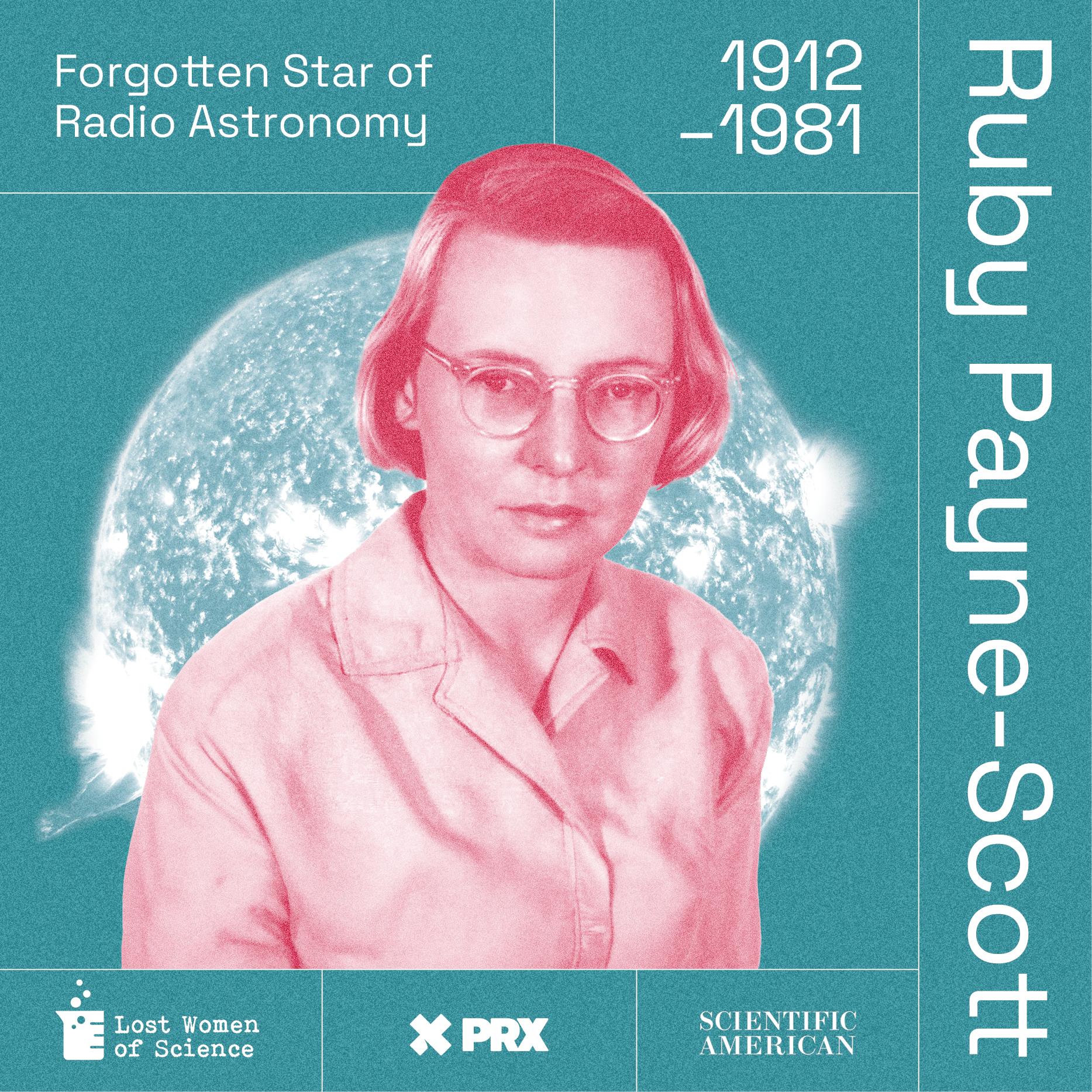

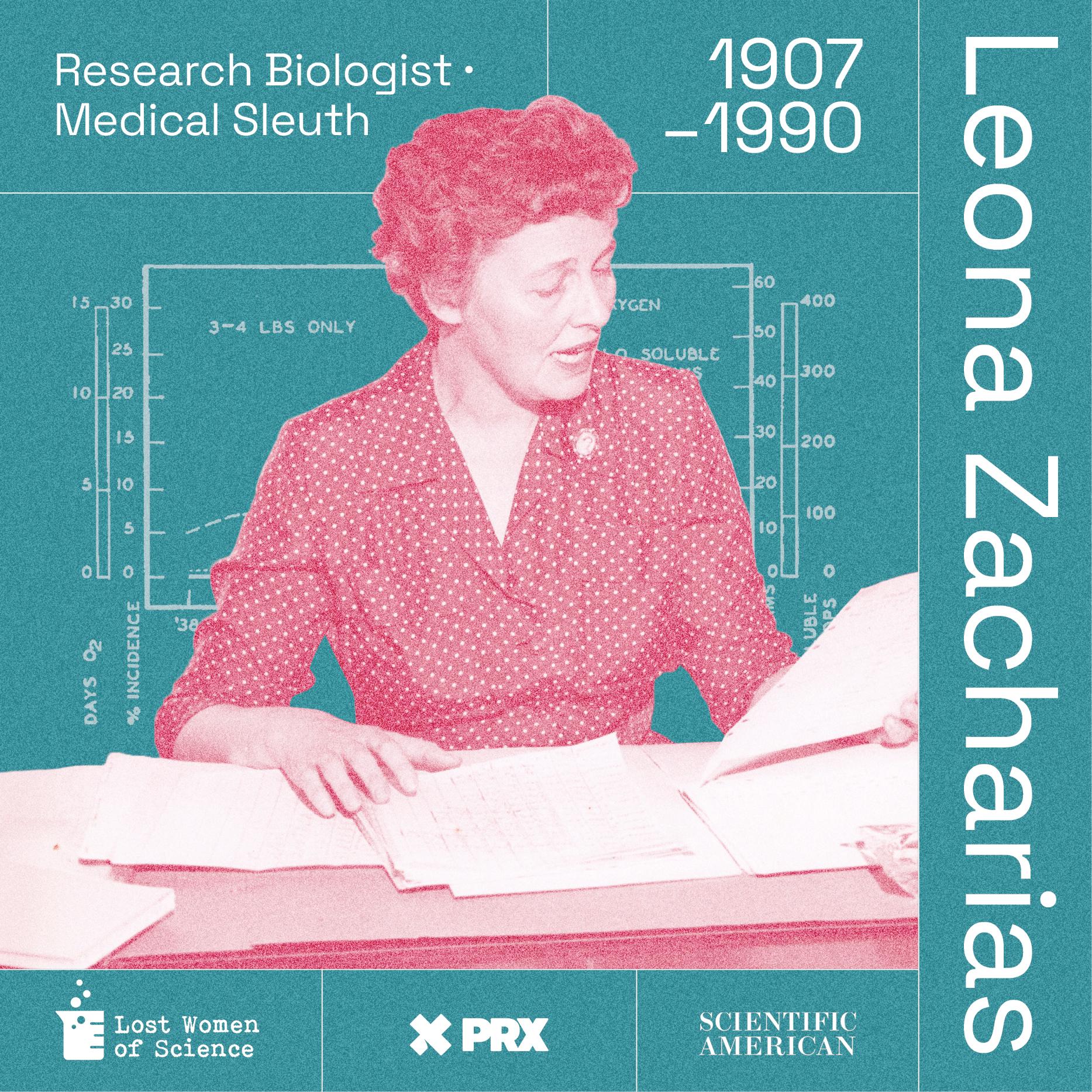

Lost Women of ScienceFor every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

For every Marie Curie or Rosalind Franklin whose story has been told, hundreds of female scientists remain unknown to the public at large. In this series, we illuminate the lives and work of a diverse array of groundbreaking scientists who, because of time, place and gender, have gone largely unrecognized. Each season we focus on a different scientist, putting her narrative into context, explaining not just the science but also the social and historical conditions in which she lived and worked. We also bring these stories to the present, painting a full picture of how her work endures.

Lost Women of Science Conversations: Writing for Their Lives

In the 1920s, when newspapers and magazines started to showcase stories about science, many of the early science journalists were women, working alongside their male colleagues despite less pay and outright misogyny. They were often single or divorced and, as Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette explains, writing for their lives. From Emma Reh, who traveled to Mexico to get a divorce and ended up trekking to archeological digs on horseback, to Jane Stafford, who took on taboo topics like sex and sexually transmitted diseases, they started a tradition of explaining science to non-scientists, accurately and with flair.

Learn about your ad choices: dovetail.prx.org/ad-choices